|

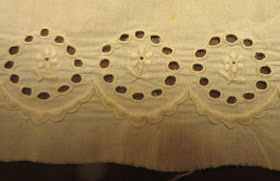

| Reverse side of piece of finely produced eyelet embroidery with new threads laid on top for comparison. Discussion below. |

(Remember, you can keep up with all of the projects on the Vernet's 1814 Merveilleuses and Incroyables Facebook page.)

Now, if the satin stitch is coarse, how are the eyelets likely to look after I finish them? I have several examples of handmade eyelet embroidery. Here are two of them: they happen to illustrate well that eyelet work appeared in both coarse and fine qualities. I do not know the age of either of the examples, and one of them may well be quite late or be a re-use of older fabric. Neither is from the early 1800s.

A Piece of Unused Fine Work

Let's start with the fine work. This is a piece beautifully worked across a piece of crisp, very, very tightly woven fabric. It is almost, but not quite opaque. The hand is hard, not soft: there are no tiny fuzzes to soften it, and the few loose threads are so, so fine, and also "hard". It has not been starched: it's naturally crisp. I haven't the heart to do a burn test, but feel that this may be a finely woven linen cambric, or perhaps a percale?

Thérèse de Dillmont's An Encyclopedia of Needlework, 1886, she recommends readers to embroider with a "loose, soft make of cotton, the looser the better, and very little twisted, is the best material for embroidery". The work being published by the DMC company, she recommends a coton à broder. They still sell it.

As for the material the embroidery is to be worked upon? She doesn't define it.

Look carefully at the pictures. Notice that each eyelet is slightly differently shaped and sized. Note that the scallops vary, too. The real giveaway that this is handwork is on the back side, though. Let's look at the reverse of one end of the piece.

What do you know? When you have a chance to look at the messy side, the thread is thicker than it appears on the front side, isn't it? You can also tell that the embroidery thread doesn't have that much twist. We'll talk about that a bit later.

In the image above, I've laid both a regular Guterman sewing thread on top of the work, to the left. To the right, I've laid the type of thread I am using to create the Vernet dress embroidery. As you can see, the original thread thickness is in between the Gutermann thread and "my" thread. "My" thread has more twist, too.

|

| "My" thread is the one on the left, marked |

If I were to try to work at this level of fineness, I'd use a fine coton a broder #25, still made by DMC.

A Less Refined Stitch on a Petticoat

Now that you've seen the fine example, what about the coarse work? Can it be there is coarser eyelet and satin stitch work than mine? Oh yes and glory be.

Here is the petticoat, a museum de-accession I picked up locally. It is closed with a drawstring, and the embroidery may be earlier than the rest of the piece. Anyone care to hazard a guess as to the age? It doesn't feel Edwardian since this sort of work was out of style by then, and in Kentucky patterns were easy to be had except perhaps in truly remote areas of the Appalachian hills.

Examine the pictures closely. To see them really close up, click on the picture, and copy the file source, and open it in a fresh tab or window. I have uploaded large files so you can do so.

Note how thick that embroidery thread is! How slapdash the stitches! Notice the thread is not twisted much, either...once again it may be like a coton à broder that Thérèse de Dillmont's talks about in her book. Embroidery thread can come in different thicknesses, and you can split the strands as well.

|

| Top row of embroidery, at top of flounce. |

|

| Second row from top of flounce. |

|

| Third row from top of flounce. |

|

| Scalloped bottom. |

|

| Back side of top row: examine the stitchwork. |

Well, My Embroidery Thread Isn't Like Either Example...

Why Not Call Eyelet Work Broderie Anglaise?

In short, I don't know, as yet.

By the time the British work The Dictionary of Needlework, by Sophia Frances Anne Caulfield and Blanche Saward, and published in 1882, eyelet embroidery was often being called Broderie Anglaise. They write that the "work is adapted for trimming washing dresses or underlinen" (p. 49). By this point, it wasn't for best wear, was it? The type of embroidery thread is to be used is not mentioned, and the entire species of embroidery gets only a short entry: it was out of fashion.

In this book, the work was to be done on "white linen or cambric" (p. 48). In another entry, cambric (Kammerack - German; Toile de Cambrai or Batiste - French), is defined as a beautiful and delicate linen textile, of which there are several kinds. Its introduction into this country dates from the reign of Queen Elizabeth." (p. 59). They also mention cotton imitations.

Thérèse de Dillmont's book, first published in France and circa 1886, lumps eyelet work under White Embroidery. She calls the holes "eyelets", and spends a bit of time, including nice clear pictures, on how to produce it. See the chapter five section on eyelets.

However, I have yet to find out what this work was called before then. We learned last post that the Journal des Dames was referring to the embroidery in April 30, 1814, as more a découpure, a cutting, than an embroidery. That leads me to suspect that this was rather a new type of work, but I don't have full evidence yet...more reading to do!

In Other News

This week I've been plagued by fatigue and a busy schedule. Life is about to get even more interesting, because to help diagnose one son's digestive issues, we're about to start a 4-6 week trial of life without any dairy products or soy products. We don't eat much meat (I hardly at all), and we do eat a lot of yogurt and cheese, so this will create a great deal of extra cooking and a deal of experimentation, and nibble away yet more of any moments that used to be somewhat leisurely. Best to roll with the punches: what else can you do?