You will want to know the basics of sewing, such as how to do a running seam, but many concepts are actually covered pretty well. The patterns are basic ones lacking fancy trimmings other than ruffles: you add trimmings as you like. The patterns can be easily altered for an adult woman, I believe. Drafts and some photos are included.

Basic pattern drafts include:

For cotton materials:

- Drawers.

- Five gored underskirt (petticoat) with dust ruffle and flounce.

- From this you also move on to make a plain five gored dress skirt, kilted or pleated skirt, underskirt with bias flounces; circular upper made from five gored skirt draft.

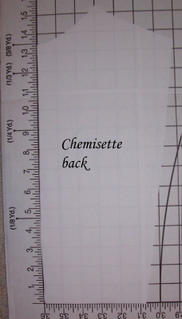

- Shirt waist draft without sleeve. From this basic draft you make also (a) Corset cover, (b) Chemise. (c) Night gown with sleeve.

- Plain tailored shirt waist.

- French (bodice) lining draft.

For woolen materials:

- Seven gored skirt.

- Nine gored skirt.

- Designed waist on shirt waist pattern.

- Coat.

The book also describes the tools and types of fabrics you need (there is also a decent glossary of period fabric terms near the book's end), how to insert boning (!), the basics of ironing, and so on.

Therefore, if you're looking to build a Titanic-era wardrobe, this is probably a pretty good place to begin.

How To Get the Textbook

Visit Hearth: The Home Economics Archive at Cornell University, at http://hearth.library.cornell.edu/. Choose Browse from the left nav bar, then browse for the book. You view and download the items page by page as text, page images, or PDF files. You can search the full text to find the pages you need. The pattern making starts around page 64. Before that you learn essential stitches, detailed handling of buttonholes and buttons, and so forth.

More about the Hearth Archive

It's a slow process digging through everything, but the archive contains literally hundreds of books about everything from sewing to childrearing to women’s wages. All with their original formatting and illustrations. Go Cornell and Ithaca, my hometown!

What if You Want to Produce Something Fancier? More Sources

- Try the Thornton’s cutting guide (1912) on the Costumer’s Manifesto, in the 1911-1920 pages at http://www.costumes.org/history/100pages/1910links.htm. Drafts for peg-top skirts, Magyar blouses, Norfolk jackets, they’re all there. You won’t find a teaching guide for making them up, however.

- VintageSewing.info has the 1917 book American Dressmaking Step by Step, at http://vintagesewing.info/1910s.html. I love this book because it teaches you, with plenty of photos, how to make about any period seam imaginable, apply the fanciest of ruffles and insertion and trimmings. I frankly do not think that such techniques had changed that much since 1911, although skirt and bodice construction had certainly morphed more than a bit.

- La Couturiere Parisienne, at http://www.marquise.de/, that marvelous site, offers pattern drafts of clothes in this period, plus some instructions for making up, and often a photo of the result. They also have a translation, from German, of portions of a book on period sewing technique, dating to 1908. Since clothes of that period were considerably poufier and fluffier and fuller, some of the instructions will not apply to 1911-1912.

- Fashion drawings and photos of actual pieces are all over the Web. Sources for these that come immediately to mind: Among the Hedgerows, Demode, Costumer’s Manifesto, Sense and Sensibility, Fashion-Era.com. I’ve also run searches in Flickr using the tag “1911” and have come up with delightful period photos of people, often in more relaxed attitudes, with their friends, than what you’d find in a portrait-style shot. You see the clothes as they were worn in action, all stretched and mussed up.

Happy sewing!